Criticism Online

A Box Built in the Abyss

On two new fictions by László Krasznahorkai.

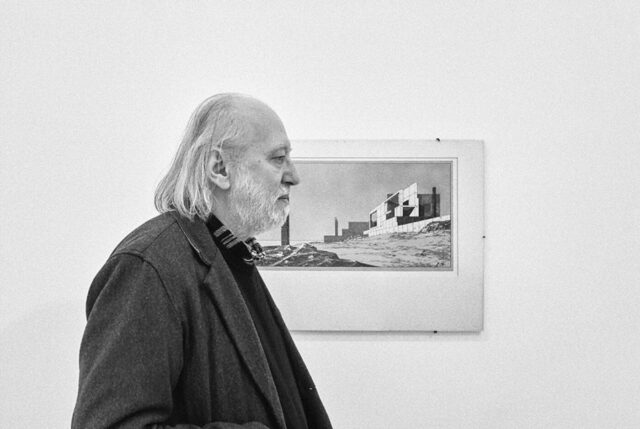

By Jared Marcel Pollen

Spadework for a Palace

László Krasznahorkai

Translated from the Hungarian by John Bakti

New Directions, 96 pp.

A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East

László Krasznahorkai

Translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet

New Directions, 144 pp.

Literature is an art of withholding. This withholding, which is one element of narrative tension, is what enables a feeling of discovery when the reader arrives at a disclosure of knowledge. Knowledge that is not discovered is simply information. Philosophy, in its more dramatic traditions (the dialogic and epistolic forms) works in much the same way: Socrates deliberately feigned ignorance in order to draw the discovery of knowledge out of his students. So too in literature: when we pick up a novel, we do so with the understanding that the author will withhold a certain amount of what they know –– that they will not say everything they can say –– and we agree to tolerate this with the expectation that sooner or later something will be disclosed to us.

In the fictions of László Krasznahorkai, everything is withheld and nothing is disclosed. The trilogy of novels for which he became known to English readers in the early 2000s –– Satantango (1985), The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), and War & War (1999) –– are dramas of the asymptotic spirit, endless searches in which characters find themselves trapped out in the open. The feeling this elicits in the reader, in turn, in one of permanent approach, like the trudge across a vast expanse toward a distant village that never seems to get any closer. This is not the work of authorial malice, but an earnest attempt to conscript the reader to share in mutual incomprehensibility, the abject failure at true knowledge that belongs equally to all humanity.

In every novel there is an object of torment. In The Melancholy of Resistance, it is a strange circus whose only exhibition is a dead whale encased in a massive container. In War & War, it is a mysterious manuscript of “no source, no provenance, no author”, which, once uploaded to the web, could become “a momentary isle of eternity.” In Spadework for a Palace (translated from the Hungarian by John Bakti), it is the dream of a “Permanently Closed Library,” a storehouse of all knowledge that will never be entered. In A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East (translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet), it is a secret garden hidden within the grounds of a Buddhist monastery.

Both novels are journeys through mental and physical space, and contain meditations on architecture, perfection, infinity, and the limits of the world (the epigraph of Spadework for a Palace is “Reality is no obstacle”). In A Mountain to the North, the protagonist, the grandson of Prince Genji, a figure who transcends space and time, wanders the grounds of a monastery outside Kyoto, a place that is itself boundless and omni-dimensional. It recalls a parable of Kafka’s, “An Imperial Message,” in which a dying emperor whispers a final message to his herald, but when the herald attempts to leave the palace to deliver it, he finds that he can’t –– passing through chamber after chamber, courtyard upon courtyard, as the galleries and staircases stack up endlessly, with the imperial capital –– “the center of the world” –– remaining forever out of reach.

As the reader also tours the monastery, the narrative becomes more and more preoccupied with the details of its construction, in which units of measurement, types of timber, weights, and ratios are laid out in rolling Euclidean descriptions. There are also musings on distance, symmetry, the highest possible number (“the LAST NUMBER”), as well as the flora and fauna that make up the living substructure of the grounds. Just as the radius of a circle contains a nonterminating sum, so too does the monastery contain infinity within a finite domain. The garden is a space of “infinite simplicity” and whoever looks upon it “would never want to utter even a single word; such a person would simply look, and be silent.” The monastery also contains a pagoda, originally designed to house the sacred relics of the Buddha. The pagoda, we’re told, “lacked any true entrance, any true door, it lacked any indication of even the tiniest genuine opening… it was a structure where no one could ever step in and from where no one could ever emerge.”

A similar image looms over Spadework for a Palace. The narrator, a librarian with plantar fasciitis named herman melvill, wanders the streets of Manhattan (a finite space of numbered nexuses) tracing the footsteps of his namesake, the other Herman Melville, while brooding on the architecture of Lebbeus Woods, the madness of Malcom Lowry, and fantasizing about the construction of a great tower, bricked-up and doorless, to house a library that will remain permanently locked. The site melvill selects for the tower is the former AT&T building at 33 Thomas Street in Manhattan, a massive, concrete monolith, resembling a fascist headquarters or a brutalist cathedral. (The real building is considered to be one of the most secure in America, having been designed to withstand a nuclear fallout, and is currently believed to be the location of a mass surveillance hub for the National Security Agency.)

The library, he envisions, will be rooted like a tooth into the rock of Manhattan, anchored in the earth as a bulwark against catastrophe, which is “the natural language of reality.” Only Woods’s apocalyptic architecture, which imagines disaster through its holistic erection of junky monstrosities, approximates this vision. Its purpose is not to be a paradise of Knowledge, but rather “everything that has to do with Knowledge.” With the elimination of the front doors, no one will be allowed to enter, and he alone will be the caretaker, or the spadeworker, of this monument. It is described as a “Veritable Block,” the “Ultimate Block,” the “Ideal Block,” “platonically ideal.” It is, like so many of Krasznahorkai’s holy grails, an object of complete blankness and inscrutability. Like Melville’s whale or the monolith in 2001, it is a black hole that sucks up our interpretation and gives nothing back.

Krasznahorkai’s prose is also monolithic. His novels contain great slabs of paragraphs, long blocks of text that seem to be broken off of a much larger mass (Spadework for a Palace, a monologue, is one eighty-nine-page-long sentence). Periods are rare, and much hangs on the comma, a form of punctuation that seems to make everything provisional. Again, there is some refusal of finality in this. Putting a period on a sentence closes it. It is in itself a declaration of understanding, that any statement can be finished with. But no statement can ever be finished with. Krasznahorkai once said in an interview, “Only God needs the period.” He has claimed that he will often compose sentences in his head for a long time before finally writing them down. This is reflected in their rhythm. They are sentences that take long walks, a feeling translated brilliantly by the long takes in Béla Tarr’s adaptations of Satantango and The Melancholy of Resistance, in which the camera follows characters for several minutes as they trudge across great landscapes.

Like Melville and Kafka, Krasznahorkai’s work bends towards the allegorical but never fully touches it, depriving us of the easy comforts that simple allegorical thinking offers. The religious mind has conditioned us to suspect that meaning is always standing-in, that something must represent something else. In Moby-Dick, this is expressed in the chapter, “The Whiteness of the Whale.” “I almost despair of putting it in a comprehensible form” the narrator says, because the whiteness of the whale is above all a “transcendent” and “nameless terror.” The notion of attempting to contain or assimilate it with a description is therefore appalling. So too in Krasznahorkai’s fictions, our impulse toward interpretation is always being frustrated by placing in front of us objects that seem to represent everything and nothing.

These objects — the garden, the library, the whale — are by their very nature, impossible to apprehend. Their “meaning” is so up front that it is actually too big to see. In The Melancholy of Resistance, when Valuska finally enters the carriage to see the whale, we’re told:

Seeing the whale did not mean he could grasp the full meaning of the sight, since to comprehend the enormous tail fin, the dried, cracked, steel-grey carapace and, halfway down the strangely bloated hulk, the top fin, which alone measured several metres, appeared a singularly hopeless task. It was just too big and too long: Valuska simply couldn’t see it all at once.

This echoes a passage from the chapter “The Tail” in Moby-Dick, in which Ishmael imagines the whale saying: “Thou shalt see my back parts, my tail, he seems to say, but my face shall not be seen.” (Itself a direct echo of the reply God gives to Moses when he asks to see his face.) The tower dreamt of by Krasznahorkai’s melvill is of course an object of Biblical scope, a Babel in both ambition and in content. It is in many ways a callback to the epic mode, where literalism and allegory are mapped onto one another. It points to the kind of “totality” that Georg Lukacs argued was present only in antiquity, when epics were characterized by the immanence of meaning in the world. This immanence is inaccessible in modernity, and because we cannot comprehend it, when we’re presented with it, its very existence menaces us.

Spadework for a Palace and A Mountain to the North both gesture toward some recovery of this, of the possibility of a window of de-estrangement, what one character in The Melancholy of Resistance describes as a “brief glimpse of ever clarifying totality” — if we are ever able to see it. The librarian never actually enters his dream library, but stands in its shadow, pondering its impossible mass. And in the monastery, we find that the garden hides in plain sight, and when the grandson of Prince Genji accidentally comes upon it, he takes no notice of it: “whoever walked inside here was already on their way out and never again, it would never even occur to anyone to return here again, and so such a person would never know he had made a mistake, a great mistake…”

The mistake is in believing that such a hermitage can be found. A garden, a library, a tower — they are all chimeras of the mind, as empty as the space that encloses them. For a box built in the abyss shelters nothing. All of Krasznahorkai’s characters are desperate for some asylum, to gain access, unaware that they are already inside that which they wish to enter. There can never be any arrival, only pursuit. They are like Wordsworth crossing the Alps, waiting anxiously for the peak, for some summit of experience, only to be told that they have already crossed the Alps, oblivious to the persistence of their own descent and the void that lies before them.