In his column “Show Me Your Hole,” Paul McAdory searches for his determinative wound.

To have at one point been religious; to have since left religion; to still grasp automatically at its handrails (hope, judgment, forgiveness, etc.) for support; to wish for God’s grace when brought low and to wonder if you don’t feel it now and again as a warm light, like from a SAD lamp or tanning bed, imitative and artificial but bright to your eyes and real in effect; to have heard in “heaven” not only “the future, endless meaning, endless narration” (as Robert Glück has it in Margery Kempe), but also wholesome family pleasure forever; to have been a child and childlike before the Lord: this can be a potent brand modifier for emerging creatives.

In a crowded field of writers, artists, and makers of every stripe, standing out from the pack can be a challenge of seemingly Biblical proportions. What sets you apart? What makes your product worth a public’s attention or, better yet, devotion? While there’s no one answer to these questions, faith and its collapse can play an important role by lending texture, dynamism, and a sense of relatable woundedness to your image. Hence why I’m lucky that my parents joined me to the Southern Baptist Church as an infant.

God was good those first years and my investment in our collaboration genuine and consuming. I loved Him and He loved me and all creation beyond my comprehension, in other words. I thought I too loved all creation because loving seemed very simple. I said, “I love it all too,” and then added, “except the devil,” and, after further thought, “also Hitler.” I was given to understand that the love I spoke did not equal that which God was and exuded — my love was like a catfish and His, the water; it sustained mine, touched mine, fed and homed it — but I neglected to allow understanding to stopper the flow of my sure feeling.

To honor Him I attended Sunday School at the mostly white First Baptist Church of Clinton, Mississippi, a suburb of Jackson (the capital) known for its Baptist college. To honor Him further and less begrudgingly I took my place at a cafeteria table there every Wednesday evening and ate pizza or burgers with other boys. They traded Pokémon and later Yu-Gi-Oh cards. The weird ones showed off their Magic. Some said “crud,” which seemed a bad word and so an exciting one. Could I say crud? Was I old enough to use it casually among acquaintances? Was it a slippery slope to crap and damnable shit? Before I could decide we’d walk to a classroom for Royal Ambassadors, or RAs, the boys’ youth group, and receive lessons on how to cultivate a personal relationship with Christ. A thin, aged, Larry David–headed instructor wrote relevant words in cursive on a chalkboard. He worked at Wendy’s. We couldn’t read cursive but didn’t especially mind. We liked Wendy’s.

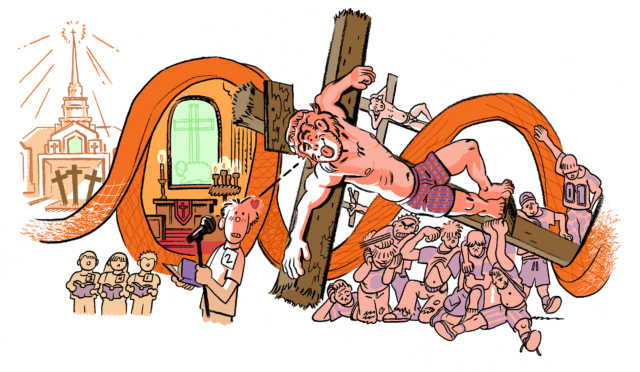

Years of easy piety elapsed. In February 2002, aged nine, I opted to be baptized in the Church alongside several other children. We took turns recording short videos explaining our readiness to take the plunge, and when the appointed day arrived each video played on a projection screen before its white-clothed subject was immersed in an elevated pool behind the pulpit. The congregation looked on from the dark, wooden pews of the two-tiered sanctuary. Above and behind the pool a dove flew in the stained-glass window, its wings extended, its white body overlaying a golden disc and licked at the edges by what looked like red-orange tongues of flame. Would the dove extinguish them or burn? Out of the pool, I felt new, renewed, cleansed. Me, at least, the flames had lost. My life had begun again. My likeness had appeared on a screen watched by a live, presumably rapt audience.

I knew Christ, then — I had accepted Him into my heart, first privately and then ritually, and thus remain guaranteed a place in paradise, no matter how I may recant or sin now, or so goes my understanding of the contract — but I didn’t know His and God’s work as well as seemed necessary for my eventual departure to achieve maximum utility. Before I left the Church and became a person who referred to it sighingly, though not without a glint of eagerness in his rolling eyes, as complexly foundational to his person, and who figured it was worth a line or two on his Wikipedia page and/or an eighty-thousand-word memoir, I would need to firm up my standing as a committed Baptist; I would need to ensure that, when I eventually lost faith, an aura of profundity, and a sense that I had undergone a radical if logical change in subjectivity, would swirl around my loss. But how?

With my fellow RAs I had gone on trips some ninety miles south of Clinton, to a more rural part of Mississippi; I had gone before other boys my age through the intervention of my father, who was friends with a man whose property and cabins provided the sleeping quarters and home base for nature excursions. At night we fed campfires that drew wide-winged moths to the cabins’ wooden sidings. The boys prodded and gawped at the insects and spoke subtly of girls, their voices trailing off into the muggy air at my approach. In the daylight we journeyed to the edge of Red Bluff, a sort of cliff formed by erosion and rendered beautiful by exposed layers of red clay admixed with sand and soil. A rope was draped over the edge and anchored at either end to make it taut and thus prevent boys from spinning round or wandering left or right. As I began my first descent, I backed toward the drop off, my fingers brushing the earth as they slid along the line until my feet moved through the open air and pressed against the blushing earth. All was well until my hand caught between rope and sediment’s edge, and as the line squeezed all sensation but pain out my fingers I wondered if I wouldn’t perish — the rest of my life contained in this tight hurt beyond my knuckles. But no. God and men were with me; they guided my hand free and I climbed into the muddy, miniature canyon, where I met the others and ventured out toward the Pearl River.

The relevance of our trips to the divine I could not fathom unless an exploration of the natural world and a nurtured closeness to other boys be deemed relevant to the divine. And perhaps this was the goal, to expose Mississippians accustomed to the state’s humdrum flatness and pine forests to a geologic formation that, though not a mountain, might inspire the wonder and awe (and terror) we expect from mountains, from the rocky heights upon which Noah’s ark had landed, Moses had received the Commandments, and Jesus had delivered his sermon. The terrain of our state evoked God’s expanse and enfolding will, which hugged us like the trees did our towns and houses, but it lacked the drama and revelation of sky-piercing peaks.

Still, experiences of nature, however affecting, seemed an abstract and potentially ineffective means of increasing my Christianity stat. Belief is not a forest. It’s a word. Faith is a word. The sermons that I heard and the lessons I learned in Sunday School consisted of: words. Words brought me close to God and would later take me away from Him; they would fashion my transformation from believer to nonbeliever into an arc legible to others. Being more Christian would mean imbibing more words, the right words; it would mean direct knowledge of scripture, of the Word. I needed to engage the holy text, to dedicate myself to its contents and through my dedication earn my coming faithlessness. At the same time I needed to maintain my proximity to a group of boys so as to keep the sexuality angle in play. The vague proto-desire I felt for my fellow RAs could then evolve into something more confused and forceful; I would be able to describe its interaction with my religious beliefs as painful and allocate to it a degree (varying depending on my audience, mood, age, whatever) of responsibility for the breakdown of my relationship to Christ. As it happened, my church offered a program that met all my requirements.

Bible Drill was a kind of Church sport wherein one learned expertly how to navigate the Good Book and memorized certain of its passages and all of its structure so that one could succeed at competitions that scaled, like high school sports, from district to state-level, or rough approximations of the same. Learning occurred at weekly practice sessions and the less frequent but desperately anticipated gym lock-ins, during which I’d dutifully radiate smothered lust while Son of the Mask played across the room.

The competitions seemed to matter. Clutching a Bible by my side, I would stand facing the judges, ready for the caller’s signal. I wanted to win “superior” ratings and did, but I cared more for another kind success, one that inhered in the accumulation of scenes, or the bare outlines of scenes, which I might later fill out using details derived from imagination and research: boys in a line praising God for the approval of judges; boys atop sleeping bags whispering “Keira Knightly”; sweaty hands fondling air hockey pucks, eyes flitting from the floating disc to the hunched body across from them; high voices reciting verses, a few of them cracking. If I squinted, maybe one of these scenes would look primal: the foosball table shuddering as we yanked and spun its metal rods, etc. I was building my lore. That certainly mattered.

Before, the great enemy that had confronted me had been my paltry shame. I simply hadn’t felt it enough. As a theme it had been teased but not developed. It did not churn disastrously inside me, poisoning me against God and Church. The struggle between bodily and spiritual wants could not play out its violent saga and I would not, as things stood, be able one day to sing its affecting song. RAs had contributed meagerly if fundamentally to my private store of mortification. Finally, in Bible Drill I found, if not the full bounty of shame I would need later to contrast with my devotion in memory, then a favorable supply of what I could strategically refer to as its seeds. On the cool gym floor I could almost ponder the feelings I almost felt for the young worshippers locked inside with me.

All that was left was erosion. I needed my belief to become a bluff. I would have some choice as to how to describe and rank the causes of its creation: sexuality and scripture generating shame, paranoia, and distrust in their encounter; the evidence of my senses and the sciences as I understood them; the imperative to change as I aged and so to look upon what I had earlier loved and believed as unlovable and unbelievable — but these are less important than the formation itself. To see it best I would throw a rope over its side and, climbing down, marvel at its rich texture and striated color. Instead of the line trapping my hand it might be a layer of sediment that caught my eye. A part of my consciousness may be contained forever in a square inch of memory, and I might elaborate on it, conveniently understand it as representing the bluff in toto or more scrupulously diagram its relation to the whole of the phenomenon before me.

I suppose God is still good. He provided for the hereafter of the zealous child I was. The future became a story I could tell about the past, and in that story the past would live forever, would become eternally present in its way, like Viacom. It would have a new body, everlasting and unfaltering, restored from the brokenness of experience to a state of narrative or essayistic wholeness that I could promulgate at my discretion and to my benefit. I hoped it would be good for me.