We deep in the summer of 1998 and it’s just turned noon when I find Rafiq lying on his bed, dirty trainers and all, throwing a cricket ball at the ceiling. If he misses it could crash into his face, break his nose.

“Ahoy,” I say.

“One love,” he murmurs, without stopping his game. He’s shut the thick curtains against the December sun, but it’s a fool’s move since the room trapped the morning’s heat. Except for the ball he’s doing deliberately nothing, and even lying down he gives off that same confidence he has rolling through a club or strolling our university campus. Not a walk, but a strut. Like God pressed play on his personal backing track and the rest of us are just the hype-guys.

“Yoh, it then stinks of weed in here,” I tell him.

Rafiq gives a weak laugh and gestures at the crushed-out joint lying in an ashtray full of smokes by his hip, “Breakfast of champions.”

“We’ll have to get rid of that before your moms come home.”

He hoists himself up onto his elbows and scrolls the joint between thumb and index finger easing off the hardened ending, sniffing to see if there’s anything still smoke-worthy. He hasn’t looked directly at me since I walked in.

“It’s kak hot in here my broe. Can’t we open a window or something? It’s full-on claustrophobic.”

“The windows are open, Mickey,” Rafiq makes a turn on his bed, “It’s just that fucking hot today. If you so hot, why don’t you take off one of those layers? You probably the only person in the whole city wearing long pants today.”

I laugh and ask what time Joe Shoes and Andy are arriving and Rafiq tells me that they’re already here, they just refuse to sit inside.

“You see? It’s not just me.”

Rafiq nods. Sometimes — not often — he’ll concede a point.

“What we going to do today anyway?”

To be fair it’s too hot to think, never mind do, but Rafiq, who takes his hosting duties seriously, sits bolts upright and says with a sly grin, “Why don’t we car-surf?”

I laugh because that’s the only way to respond when he’s like this, when he comes at you with outlandish, dangerous-sounding shit that spells an afternoon of cuts and trouble.

“What?” I ask, and then, instinctively, “No.”

His grin vanishes. For a golden boy, he’s got a short fuse. He’s always had this capacity; he can turn on a bra, ruthless, make him into nothing if he wants to, just with words. Kyk vir Mickey, he might say, Kak boring like that.

You could be a lot of things around Rafiq, but you couldn’t be boring. If you were boring, you could be left stranded on the curb. He would not pitch to give you that lift he promised, or he’d give you a miss at the movies. I didn’t see you, he’d shrug.

And what is there to say to that? If someone says they didn’t see you, they didn’t see you, and no amount of standing in front of them waving your arms is going to change that.

Just don’t be boring, I’d say to myself before we saw each other, whatever you are, don’t be boring.

So when he says again, “Let’s car-surf,” this time with a serious edge, I don’t question him. I pretend like I understand perfectly what he means, that I think it’s a cool idea, that whatever it is, I’m down with it. I’d only just started hanging with this crew after a long high-school exile and I didn’t want to fuck it up. We were all tight once — me and Rafiq and the boys — and I’ve been banking that the history that brought us together will keep us together. Though I also know I shouldn’t rely too much on history; there’s a lot of it going around this country and most of it bad.

“I’ll call the others,” I say.

But Rafiq’s already strolling ahead of me, shouting at Andy and Joe to meet us outside the house.

We all from the same part of Cape Town, give or take a few kilometres, me and Rafiq and Andy and Joe Shoes. All from respectable Coloured neighbourhoods, close enough to the gangs to be careful, far enough to never really have to worry. We easy, cool with the White and Black kids on campus, but we only hang together. Like they do. Elective separation. Sometimes, when I look at my crew, all of us from the same world, I think, they really didn’t need to go through the bother of legislating that shit, look how we peel off into these groups all by ourselves. I said this to Rafiq once and unusually for him he got serious and quiet, saying that we do that shit because of history, not despite it. Maybe he’s right. Because it’s fucked up, like only hanging out with like. Not that any of us look alike. We don’t. Joe Shoes is light-skinned with eyes his girlfriend likes to call “hazel,” Andy (the only Christian boy in our crew and the prettiest) has been diving deep into his Griqua ancestry lately, and Rafiq’s so tall that if we want to piss him off, we tell him he has Dutch blood. Not that he looks Dutch; he looks like some of his mother’s people — Indian — with his inky black hair and brown skin. But what do any of us know about looking like we from one place? In the Cape, we know that’s the lie that keeps on giving and living.

We all outside now and Rafiq’s in lecture mode: feet apart, cigarette gripped between his teeth, hands splayed, read to hold forth, “Ouens,” he says, “Car-surfing is befuk. Trust me.” And then with a wink, “We can use Mickey’s mom’s Beemer.”

My mother’s car? Fucksake. I still don’t know what he’s got planned and I can already see the accident, the dent, my mom’s losing her shit, but I’m ready to do anything to stay in the circle. It’s Joe Shoes (aka Yusuf Arriefdien — his daddy had made a fortune in footwear) who says he doesn’t think it’s a such good idea.

“Naai man, Rafiq man,” says Joe Shoes, who knows all about car-surfing, “You gonna mess up his mommy’s suspension. Use your own car if you want to do this… Also, I want it on record that I think it’s kak versin.”

Joe Shoes is forever putting things on record as though that’s going to exonerate him when things go wrong later.

I glance at Joe praying my relief isn’t showing on my face.

“Relax Joe,” Rafiq says, “I’m low on petrol, but we can use my car if you so concerned. Mickey, you can still drive.”

Rafiq’s got one of those small dark green VW Golfs that everyone on campus seems to have these days, and Rafiq bitches about it All The Time. It’s a girl’s car. It’s got no power. If his parents really wanted to keep him safe, they’d buy him something bigger, faster, something that didn’t feel like it was going to fly apart when he pushes it down the M5. I think it’s a crazy argument, but Rafiq is set on it. He believes it so deeply that he even made it to his moms one day. Her head whipped round. She stopped what she was doing and said, Now I’ve absolutely heard it all. Not in all my days did I think a child of mine could be so bladdy ungrateful.

But Rafiq, who is charm with everyone else, held his mom’s gaze without his usual smile. He stood there, waiting for her to talk, or maybe trying to keep her talking to him, but she was already worrying about what time to collect his baby sister. He walked off and when their backs were turned to each other, she called out, And you shouldn’t even be speeding. More powerful car my foot.

She’s right to be angry I think now, getting in the car. He doesn’t even take care of it. “It’s filthy in here bra,” I tell him.

There’s mal-pitte, shiny sweet wrappers, a KFC box, cigarette butts bursting out from the closed ashtray. And just like his bedroom, it stinks, like someone has been smoking in there for a thousand years, made worse by Rafiq spraying his dad’s Old Spice everywhere.

“Now what?” I ask, settling into the driver’s seat.

“Get ready to drive an ordinary vehicle under some extraordinary circumstances,” says Rafiq.

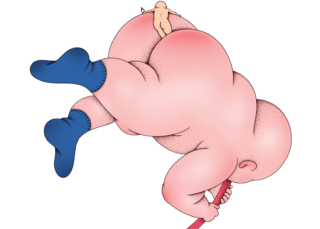

I put my hands on the wheel, foot on the clutch, breath tight in my chest and watch, wordless, as Rafiq climbs onto the bonnet, lays himself flat, grips the window-wipers, and lines his face up with mine.

“What the fuck.” I lean out the window. “At least have the sense to lie in front of the passenger seat. I can’t see anything with your big-ass face in my way.”

He laughs and moves to the other side. “Go. Go!”

I go. Slow as I can, cruising the flat streets, passing the respectable houses and their square-patch front lawns, just touching twenty kays an hour when Rafiq shouts above the hum of the engine, “Faster man Mickey man, faster.”

It’s like I’m driving through an inferno. The car’s got fuck-all AC, it’s been baking in the sun the whole morning, and I don’t know how Rafiq is surviving on that bonnet. You could fry an egg on it. Shoes and Andy are rollerblading beside us, and I feel like I’m living two lives at once: I’m driving but I’m seeing Rafiq slide off and roll under the car, the wheels turn over him, his body in a crumpled heap, myself at his funeral, not being able to face his parents. Then in jail for manslaughter, facing God-knows-what, the stuff of my nightmares in prison, and the whole time he is just laughing and telling me to go faster. We pass a couple of his neighbours watering their gardens, washing their cars. Occasionally, Rafiq breaks a hand away from the wiper to wave like a beauty queen and I feel like I’m going to have a heart attack. Ahead, mercifully, is a stop street. I’m so done with this stupidity, but Rafiq is banging on the glass.

“Make a left” he says, “Make a left right here.”

“Which is it? Left or right?”

“Don’t be versin. Left! I said Left.”

I obey and Andy, who never passes the opportunity to make this joke, says, “Right you are” and then laughs like a nwata.

It’s a busier road, still residential, but I’m nervous as hell and my breath is getting more shallow by the inhale, even as Rafiq is goading me, faster, faster.

Fuck it; I accelerate. With each kilometre gained, my panic increases. Just as I think I’m going to have to choose between obeying Rafiq or killing him, his car decides for me: first spluttering, then a couple of lurches, finally, it just stops dead in the middle of the road.

“No petrol,” I announce, trying to keep the joy out of my voice.

Rafiq rolls off the hood, steadies himself and then shoots his head through the driver’s window, his breath on my neck, hot and close, saying “Already?!” He says we should keep trying, that we shouldn’t quit now, and that if his car is on the brink, we should use my mommy’s. But Joe Shoes says he won’t do that “on principle” and Andy says car-surfing looks kak uncomfortable, that it’s vrek hot anyway, and nothing could persuade him to actually put himself nearer to heat.

“Game over,” announces Joe Shoes, and Rafiq’s scowling because it’s his house, his car and he should be the one calling the shots.

We push the car back to Rafiq’s house. Obviously, this time he’s in the driver’s seat. “If we’d thought ahead,” Joe Shoes huffs at the rear, “We could have asked some girls over. Varsity holidays and no-one’s parents are around.”

But Andy insists it’s too hot to do anything with girls anyway, that the only thing worth doing is lighting up and lying flat on the cool tiles in the kitchen. “You have to wait the sun out,” he reasons, “You can’t challenge the unchallengeable.”

If Joe’s about putting things “on record,” Andy is forever in the habit of making a theory sound like a fact. It can be annoying when you’re sober, but he sounds like the Dalai Lama when we’re stoned. Which we are, mostly.

We get to the house and out of nowhere, Joe Shoes asks how Hassan is.

For a second I think Rafiq is going to punch him.

Hassan is Rafiq’s older brother and he’s been in America since the eighties; he’d gone into exile when he was just a teenager — for being what his father called a “troublemaker” back then and calls a “hero” now. We heard that before he ran, he spent some time in jail, in solitary, where he was knocked around — and maybe more.

Rafiq doesn’t even look at Joe, he just unlocks the gate and says, “Ah, fuck him man.”

It takes a lot to shock us, but this does.

No one says anything, not even Joe Shoes.

Back when we were still in primary school, Rafiq talked about his brother nonstop. Always going on and on about some mythical trip he was going to take to the U.S. to visit him. He’d tell us that Hassan sounded like a real American, that he played basketball and ate chips (no, fries) whenever he wanted to. Rafiq would hold court about him, this American brother, all dollar-fresh and free. The whole thing gave him a cool authority that no one could challenge.

But Rafiq never visited New York and Hassan never came home and then, in high school, after the ’94 election, Rafiq stopped talking about him. If he did, it was to call him fake, a phony, that he was just this bra who didn’t know anything about home, who didn’t care about his family or his people, and if he didn’t want to come back these days when everything was cool and we were free then it was his loss. Instead of losing points because the trip never happened, everybody seemed even more in awe of Rafiq, like he was flexing some amazing power: not only did he have an American brother, but he could shrug him off too. He didn’t seem to mind saying it in front of his mother who would wince and say, Rafiq, Rafiq, you mustn’t talk like that, or she’d run off and find something to do in the house. She still used that respectful voice South Africans use for people when they’re sick, or religious, or they live overseas. His father would just walk away or pretend he didn’t hear and I sometimes wondered if he shared Rafiq’s view, or at least the ache behind it. That man treated Hassan like he was an invisible fire in the middle of their house; edging around it, never through it, as if engaging would make the fire bigger, wilder, tear right through everything.

So we knew Rafiq was angry with Hassan but saying, Ah fuck him, was next level.

Plus, I can’t believe Joe Shoes would ask about Hassan so casually — like he was asking the time.

But Joe keeps going: “You know ne? My parents were just saying now-now the other day how long it’s been since he left.”

Rafiq’s jaw is clenched so tight I swear his face might crack.

I could kill Joe.

I only ever check in about Hassan when Rafiq and I are alone together, when we ditch the clubs for the night, when there are no beats or pills or white girls trying to massage our shoulders into an e-high. I’m careful, you see, when I ask. I think about it. About him. I plan it. And it’s paid off because there was one night, months ago, when it was just us, that he said a lot.

He told me that in the weeks after jail and before exile, when Hassan was finally back home, that he — Rafiq — didn’t sleep at all. Not because he was worried — what did he know as a seven-year-old kid? — but because they still shared a room and every night Hassan would wake up at the same time, like clockwork, screaming. And every night their mother would rush down the corridor — her hair a mess, her face ghost-pale, her own sleep and dreams still clinging to her — to hold Hassan, crying, panting by his side.

And you? What did you do? I asked him.

Nothing, he answered.

He just lay with his back to them, wide-eyed in the dark, knees to chest, shoulders curved, fists tucked tight, pretending to be asleep.

It was a one-off thing, he never opened up like that again and I got it. Really. Because what was there to say? What is there to say? You peel back a little at any family in this place and we all got some fucked up story or other about what it was like to live like that, and like that wasn’t even so long ago.

Inside, I’m rolling up a storm because I’m the one with the smallest, quickest fingers. Rafiq once told me that I must have extra oils on my tips because every one of my joints is perfectly formed.

An hour passes or maybe only five minutes; either way I’m hazy. And I’m grateful the day’s got a little more ease to it; the biggest decision ahead of me is water or cooldrink, chips or chocolate.

“Did you hear about that Mickey? Mickey? Mike? Check this bra. So toast so he can’t even hear his own name.”

It’s Rafiq.

“What? What now?”

“You know Peanuts from Fourth Street? He was caught getting it on with another boy so his brothers fucked him up so badly he’s in a wheelchair. Their moms went bedornet, threatened the brothers, sons or no sons, said she’d report them straight to the police and they served her up some bullshit about doing their Islamic duty.”

“Yoh,” says Andy, “That’s heavy. Why mus you people be so hectic man?”

“What people?” asks Joe Shoes, leaning in, his body contracting very slightly.

“He means Muslims,” says Rafiq, though none of us needs the clarification.

Joe Shoes is big on taking offense these days and I can see him gearing up to fight with Andy, riling himself into a state because Andy’s already launched into his thing about fundamentalism and just letting people be.

I know for sure that Joe Shoes doesn’t believe any of that shit about hellfire and cruelty, but he’s gotten so fucking defensive lately. He’s about to pop off, when Rafiq, always ready to undercut anything too serious, breaks into a laugh, singing, “The fundamental things apply, as time goes by — ”

It was funny and it should have worked but Andy’s too upset by the story to let it go.

“It’s not right,” He directs this to Rafiq, ignoring Joe Shoes. “It’s a fucked-up thing to do to someone. Crazy people running around, acting like they the morality police, like they real life bogeymen.”

“They don’t even know from Cape Town,” says Rafiq, as though he knows everything about everyone in the city, “That’s not how we hang. We chill here man. We don’t need their Wahhabi noise fucking up our game… They must just try something like that with a bra of mine.”

Like most things, Rafiq does bravado well. As if to match action with words, he picks up the knobkerrie that his father keeps by the sliding door and passes it back and forth between his hands, getting the measure of it. And even though Andy’s laughing and chanting, “Aweh Rafiq,” I know Rafiq’s bullshitting. His hands are shaking.

Joe Shoes’s face is one big sneer, and then fast, no warning, Rafiq makes a dive for him. He wrestles him off the couch and flings him on the ground, gets Joe on his back, sits on top of him, legs sprawled on either side and starts grinding away. Joe yells at him, furious and writhing, calling Rafiq every filthy name under the sun while Andy is laughing so hard, he can’t speak, just clapping his hands together like a seal. Joe’s trying to push Rafiq off but Rafiq’s bigger, stronger. He leans down threatening to kiss him unless Joe admits that what happened to Peanuts from Fourth Street was fucked up.

“I never evens said anything,” protests Joe.

“But would you stop it?” Rafiq presses his crotch against Joe’s and leans in to bring their faces level.

“Stop what?”

“I’m asking if you would help a bra? If someone was attacking him like that? For doing that?” A look of disgust slides over Joe’s thin face. He draws a sharp breath before laying each word out like a commandment, “Not. A. Fuck.”

Rafiq’s sits up and grabs Joe’s slender wrists, holds them together then separates them out, slamming one hand onto the floor on either side of Joe’s head. Joe whimpers and appeals to Andy, but Andy just says on repeat, “You reap what you sow bra.” Besides, Rafiq hasn’t stopped questioning him.

“What if the bra was your bra?”

When he wants to know something, Rafiq can repeat a question fifteen different ways.

“What if the bra was one of us? What if he was Mickey?”

The room turns as one to look at me, and even though it’s hypothetical, even though Rafiq has said my name to make a point, even though he’s laughing now, my chest explodes in shame and fury. The silence from Joe builds and builds, fills the whole room until Rafiq gets up, bored, strumming his own chest with his fingers, brushing Joe’s touch from his body. Joe just sits there, sore inside and out, massaging his wrists, his fury bouncing off Rafiq’s back.

We all know that next time, he’ll think twice about asking about Hassan.

It’s dead quiet and I worry they’re going to turn to me again so I say: “What’s the plan ouens? We just going to stay here all day?”

Rafiq pinches the bridge of his nose and shuts his eyes as though communing with an idea. Then he announces, triumphantly, “We going to Seapoint Pools.”

We groan. United for once. We talk in and over each other: it’s already past twelve, the place will be packed, there’ll be no parking, the kids will be going bedornet. Rafiq, why? You not thinking bra. Long-ass queues, sweating us in our chops. All the way to the other side of the city

“Plus,” adds Joe Shoes, still steaming, “I just got my hair cut and styled yesterday in case no one noticed.”

But this is Rafiq’s idea, so we end up exchanging some bottles at the garage for petrol money. I’m at the back and Rafiq keeps catching my eye through the rear-view mirror, as though we’re in on a private joke. Joe Shoes is up front complaining about how poor the car’s speakers are, when Andy turns to me quietly, “Bra, you not hot in that long-sleeve?” and I tell him it’s all good, that covering up is standard practice in other hot places and unlike the rest of Cape Town, I don’t believe in wearing basketball tops when my feet have never touched a court. Andy gives me one of his soft smiles and says, “Okay, cool. Understood.”

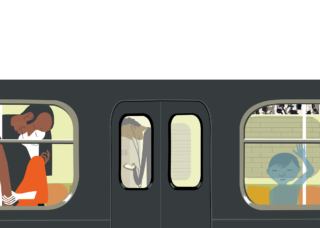

It’s less than half an hour before we get to Seapoint, but like Andy says, it’s another world, this part of the city. It’s right on the cool blue edge of the Atlantic and it’s all water and mountain and crazy-priced homes. The only reason we know it is because the pool is one of the only places we were allowed to go in the old days.

It’s a hunt for parking and as Rafiq circles, Joe Shoes points at an ocean-facing apartment block, saying, “I’m gonna make my daddy buy something here soon. No way these fuckers going to keep this all to themselves anymore.”

We finally get in and it’s a scene. Little girls in pink polka dot bathing suits holding on the sides, crying that their armbands are going to deflate. Their older sisters spilling out of their tops, with dipped waists and bikinis splicing against their asses. Parents sitting on the pool steps, shouting at their kids to bring them a cooldrink. Old white ladies with thick goggles and nervous mouths doing a slow breaststroke. A steady hum of talking out of which, every few minutes, a voice crashes, “Kyk hie, Kyk hie! I’m gonna dive now-now!”

I hate this kind of thing, but Rafiq loves it, believes he belongs to it. He strips down to his shorts and makes a cool, clear Model C school dive into the blue. Seconds later he crashes up through the surface, drenching a kid nearby, “Jy,” shouts the child’s mother, “Watch yourself!”

“Love it,” yells Rafiq, “Befuk.”

Andy and Joe are already in the water. Joe’s trying to make sure his hair doesn’t get wet, while Andy is charging at him.

I sit on the grass several metres from the water, down to my T-shirt now, two blooms of sweat beneath my armpits. Fan-fucking-tastic.

Rafiq appears at the foot of my towel, his body outlined by the sun, holding out his hand like an invitation to swim. It’s the wrong moment and the wrong question, but I can’t stop myself, “Are you really over Hassan not coming back?”

Rafiq’s not taking the bait this time. His eyes widen just a little, “Ya, it’s fine. I got you guys. I got my brasse.”

He reaches for me proper now and when I bat his hand away, he tugs hard at my T-shirt. I push back, feebly, stupidly, knowing he’s so much stronger than me. He laughs, “Come man. Get undressed. Get in the water.”

Rafiq is pulling me and I’m trying to keep sitting and while he doesn’t seem to clock the panic that’s flooding me, other people are starting to notice: kids who have an instinct for danger, moms making eyes at their husbands to step in because I’m saying “Let go man” like I really mean it. The old white ladies move to the opposite side of the pool, shaking their heads even as they paddle, probably on their way to tell the lifeguards. But Rafiq is oblivious, “Come on,” he keeps repeating, laughing loudly, getting me right up to the pool’s edge, threatening to toss me in. I’m fighting him harder than he can ever know or understand. It’s everything I got when I shove my elbow into his stomach. And he drops! Doubles over, wheezing, winded. It’s a while before he gathers himself to look up at me, eyes wide with shock and hurt.

“Yoh bra,” he manages softly, “What you do that for?”

I go towards him, still panting myself, “Sorry, sorry.” I put a hand on his shoulder but he shrugs it off, fierce and angry. “Rafiq—”

“That’s fucked Mickey man. I was just playing. You—”

“Rafiq,” I take a breath, “Rafiq—”

He shakes his head at me, one hand splayed out as though he is warding me off, the other still at his stomach, holding what hurts. Rafiq has certain codes by which he lives and elbowing a bra is a total violation. It’s up there with jolling with your boy’s sisters — you just don’t do it. I know that unless I can explain why, he’ll be done with me.

Another breath.

Another.

Eventually, I drop down to a whisper and I tell him, “I don’t like the way I look.” I put my hands on the bulges round my stomach.

He squints, waits for his breathing to slow. Then he smiles and says, “Bra, this isn’t Clifton Second where you need to worry about that. Come on man. You must be kak hot. Just get in the water. As soon as you out, you can put your top back on.”

He’s holding my gaze tight, close, trained on me, and it’s all I can do not blurt out, Whatever you say. I strip to the waist and just as I’m feeling the regret build up, Rafiq points at my left arm,

“Yoh bra! When d’you get that? That’s befuk.”

He’s talking about a scar from a childhood burn. It’s thick, pale, and raised above the rest of my skin and I hate it. I look at him like he’s crazy but Rafiq’s staring at it like it’s a work of art, bouncing around me, saying, “It looks like a tree branch, man. You should get a tat right there, or make it tribal. You look like a warrior bra.”

He hooks his arm around mine, touching the same elbow that winded him, his torso lined up against mine. He’s cool to touch, dripping water and making a small puddle around our feet — relief from the blister-hot cement. He scans the pool and then shouts, “Now!” We dash forward, bound together, breaking the rules. Rafiq shouts a warning for people to stay clear.

Below, the sudden quiet of water, the slowed-down other-time of it: dappled skin, an underworld of bright shorts and bathing suits, closed eyes, legs kicking, arms twirling, the fight to breathe, to stay here. To stay here.

On the way home, it’s me who rides shotgun. Rafiq shuts down any debate saying I’m the only one who had offered him petrol money for the trip. I hadn’t and I am about to start searching my pockets for change when he winks at me. The others don’t see it, so I chime in confident-like, “Ja. Exactly.”

Rafiq’s profile is tight and jumpy and I can see that, for him, a high point for the day hasn’t been met. He’s blasting music through the tinny car speakers, rapping loudly, keeping pace with Tupac’s flow and I see an idea come to him. I see the pleasure, the thrill of it. He slows down — we not yet on the highway — and pulls off to the side. Joe Shoes and Andy yell out, worried something is wrong. Rafiq ignores them and asks Joe Shoes to pass him his rollerblades. Bewildered, Joe hands them over and when Rafiq puts them on, Joe flings himself on the backseat, saying he wants nothing whatsoever to do with what is coming. Andy starts to lace up too, but Rafiq says, “Andy, bra, let Mickey have your blades there. Come Mickey. We in this one together.” He tosses his keys to Joe Shoes along with instructions about where to pick us up.

Next thing I know we are standing on the grass verge, right by where the highway starts, a two-laner. We both on blades, three inches taller now. Rafiq is steady, I’m not.

“Rafiq, bra,” my voice is thin with fear, “We not gonna blade against the traffic. We’ll get slaughtered.”

“Not against them,” smiles Rafiq, “With them.”

“What?”

“We gonna build up speed and then catch a lift off one of the trucks. There by the traffic light. Surf the speed.”

He points up ahead to a four-way stop beneath a bridge.

“Are you befuk?” I ask, the panic climbing from out of my head and into my voice.

“We’ll time it. We’ll watch for when the light changes, then we’ll blade up to the truck and hang on. Just do it till the next traffic light”.

“Rafiq I won’t — ”

“Don’t be like that man, Mickey — ”

“Rafiq — ”

“It will just be us. Joe and Andy are too chicken shit. I know their styles. Come on.”

I’m trying to balance on my blades, hold myself still, thinking about how Rafiq always smokes a joint down to the last inhale almost through the filter, how he dances harder and longer than any of us, throws the cricket ball closer and closer to his own face, how he once held his hand over a lighter to see how long his flesh could stand the flame, how he drives like a mal-kop on the highway, how he said, Ah fuck him, and now this, now this.

I’m hanging onto the back of a truck trying to keep my legs from the singe of the exhaust, trying to stop myself from buckling from underneath the pressure of my shaking muscles, feeling the back of my hair lift and a part of my neck that I never even knew about get hit with a blast of air that goes right inside my skull. Rafiq is screaming just one word over and over and over again, “Befuuuuk,” drawing out the second half until it is just one long vowel. I can’t look at him, can’t turn my head, all I can do is look at my hands, at the skin stretched tight across my knuckles, steel almost melding into me, and our fingers touching, feeling the same thing.

We’re gathering speed and for once, there’s nothing in my head. Rafiq manages to turn to me to me in the middle of one of his screams, offering me a smile, fucking nuts and triumphant at the same time, saying, Scream man Mickey. Let it out. Just fucking scream. I do.

I do.

We stop at a traffic light, let go of the truck, and topple towards the grass strip between the highway lanes. Our legs are shaking. Even when we lie down, they shake. We collapse in the exact same way, legs splayed, arms in a Y above our heads. I can feel each muscle, each strip of sinew as though it’s a live rope. My blood is pumping hot and close to the surface. I raise my head to look at Rafiq, every atom in my body humming high. I turn towards him, my heart beating so deep and so fast that it lifts the skin off my chest. My face, his face. My face, his face. For a moment our noses almost touch, our eyes squint in unison and I dream about taking my shaking hands and stroking his cheek.

We stay, just so, eyes tight, breath on breath, until he says, smiling, head shaking just a little, “Yoh man, Mickey man.” Then he turns to face the sky, offering up a faint laugh while the cars on the M5 tear away, hurtling past like small, brief tornados.