Book Review Online

This Invented Nation

On Mircea Cărtărescu's novel Solenoid.

By Federico Perelmuter

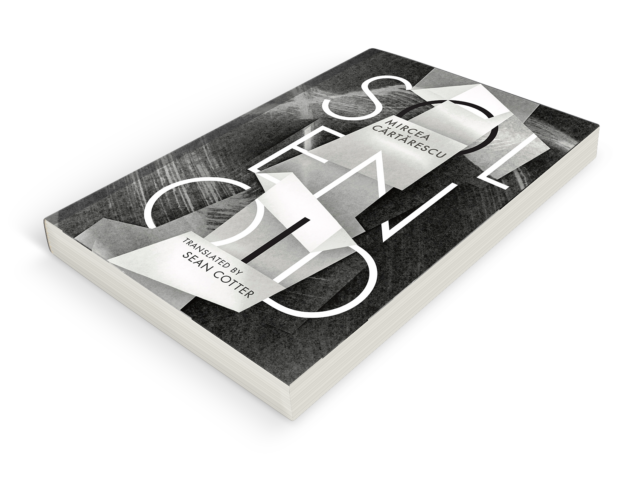

Solenoid

Mircea Cărtărescu

Translated from the Romanian by Sean Cotter

Deep Vellum, 672 pp.

Wolf! cries the boy. Innovation! croaks the critic. People like me are mostly full of shit, so take the following with a grain of salt.

Solenoid, Mircea Cărtărescu novel from 2015, newly translated into English by Sean Cotter, is something of a masterpiece. Written as the diary of a failed poet turned disillusioned teacher in the eighties in Bucharest, Solenoid synthesizes and subtly mocks elements of autofiction and history fiction (more on this later) by way of science fiction. The result is unlike any genre in ambition or effect, something else altogether, a self-sufficient style that proudly rejects its less emancipated alternatives. This isn’t pure fiction — David Shields would throw Reality Hunger, his 2010 manifesto for “reality-based art,” at my head for claiming such a thing exists — but fiction enamored with itself, that recycles its techniques in pursuit of self-emancipation. Solenoid is fiction about fictionality, which recasts Cârtârescu’s previous work and, from a new blueprint, Frankensteins a world beyond promises of authenticity or haunted fragments of the past.

Cărtărescu’s fiction has always begun with the events and atmospheres of his life. His first story collection, Nostalgia, won a barrage of awards and was published in English by New Directions in 2005; Blinding, the first in a masterful trilogy, came out with Archipelago in 2013, also in Cotter’s tasteful and perceptive translation. Nostalgia mostly deals with the experience of childhood, though its most famous short story, “The Roulette Player,” takes Russian Roulette towards its Gogolian, carnivalesque extreme. Blinding centers dreaming and Cârtârescu’s mother, two focal points of the author’s oeuvre. The other books in the butterfly-shaped Blinding trilogy center the narrator and the narrator’s father, respectively, though they’ve yet to be translated into English. Solenoid in turn moves past adolescence into adulthood, the horrors of routine, love, and non-exceptionality. The question at the center of this novel could perhaps be formulated thus: what madness lies hidden in the unremarkable?

I can only offer a roughshod plot summary. Solenoid is sprawling and mostly plotless for its first four hundred or so pages, which invoke a Proustian working-class childhood fantasia in the wintry streets of the impoverished Bucharest of the sixties, around the time Nicolae Ceaușescu came to power. The novel begins with a brilliant bit of ironic foreshadowing: our first-person narrator, literally navel-gazing, discovers what appear to be an infinite number of small pieces of twine, like sections of narrative, protruding from his belly button. They’re reminiscent, too, of an actual solenoid, a coil-shaped magnet used (most famously by Tesla) to conduct electrons across clearly defined paths. Attempting to explain why that odd string-related experience inspired his diary, he says: “I want to write a report of my anomalies,” a log of rarities like this one — not the first, certainly, or the last. This diary, mind you, is not literary (“a novel would muddy the facts, would make them ambiguous”) since our narrator is, above all, a failed poet who will soon fill hundreds of pages with mundanities. In college, following a childhood and adolescence spent reading loaned books in the half-light, he writes a long, epic poem titled The Fall, meant as a magnum opus. His reception at the main literary gathering in Bucharest is nothing short of atrocious and he vows to never write again.

A sense of half-reality lingers upon these pages. The Fall greatly resembles Cărtărescu’s most well-known book of poems, The Levant, which he published in 1990, and had previously read at a workshop named like the one in the book, the “Workshop of the Moon.” Even the poem’s original writing — longhand, with little editing — resembles Cărtărescu’s own authorial process. This is no autobiography, though; as he’s written elsewhere, the reception of The Levant in the workshop was rapturous and catapulted him towards his successful literary career. Our narrator is counterfactual; Cărtărescu’s shadow. He is an unsuccessful writer consigned to a life of ignominy, teaching in Bucharest’s Colentina neighborhood, where Cărtărescu himself worked for a time, living in a house on Maica Domnolui Street, where the author also lived. The very things that made Cărtărescu the writer of today are repurposed, and now reflect their opposite, constructing a failed imaginary writer. Not mundane, by definition, but almost.

Fiction infinitely redoubles our world. Letters, stories, memories, diaries, treatises — nothing is safe, everything shall be made useful and new. Unimaginative and conservative critics often fear the intrusion of “reality-based art” into what they imagine to be invention’s purified province. In Reality Hunger, Shields suggested that non-realist reality has been the dominant aesthetic of the internet era: texts (his analysis ranges from novels to stand-up comedy) appeal to history, photography, biography, to what we take to be “real,” to build themselves. Some contemporary authors, like W.G. Sebald, V.S. Naipaul, Olga Tokarczuk, Fleur Jaeggy, or Benjamín Labatut position their work across the supposed boundaries between the literary and the historical or scientific, a genre I term history fiction (not to be confused with historical fiction à la Hilary Mantel). Autofiction, whatever it is or was, crisscrosses the alleged truth of autobiography with fiction’s sophisticated artifice. Think of Karl Ove Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk, Sheila Heti, Teju Cole, Mario Levrero, and so forth.

For Shields, readers of nonfiction are “always and everywhere dogged by epistemological insecurity,” forced to imagine virtual texts and alternative accounts. “Reality-based” fiction destabilizes the comfortable universe of realist fiction by importing non-fiction’s neurotic relationship to “reality,” and inspiring critical reaction around the questions of historical distortion and excessive disclosure. Critics, in turn, became enforcers. They police generic boundaries, responding with rage or contempt to fiction’s brutalizing of veracity, accusing authors of sophistry for their lack of historical context or the misappropriation of facts. Some have altogether exchanged criticism for truism, as evidenced in The Drift’s recent forum on “contemporary literature,” which, among other vapid provocations, included the redundantly tepid “literature is cyclical,” and “soon we will be blessed with some new form to shit on.” There was also a review of a government document as though politics and literature were one and the same (using a nationalist, collective ‘we’ that half-self-conscious critics surrendered in the 80s) and extensive discussion of books published decades earlier, more a sign of critical abdication than literary scarcity. With exceptions, critics find little to say of contemporary fiction’s all-important relationship to reality, it seems, except when writers mess with history books or their spouses. Autofiction, meanwhile, bores even as it enchants, and often incites befuddlement when it makes writers inseparable from narrators. Any committed reader of fiction will know that for history one should read historians, and that if writers want to give themselves familial headaches or divorces for what they write, they should feel free. There’s ethics at the border between writing and life — regarding credit, for instance, or money — but if you, a reader, can’t handle fiction, then don’t.

In any case, I agree with some of The Drift forum’s prognoses — autofiction is dying out, history fiction endures for now, and realism is still kicking. Solenoid’s avowedly half-real, semi-historical approach, however, evades this provincial contemporary triad through which U.S. critics insist on reading even their best authors. A dialectical step forward, or at least a bloody good read, Solenoid combines Knausgaard-esque ambition, Borgesian sophistication, and Nabokovian delirium to puncture whatever critical paradigms one attempts to impose.

Solenoid fictionalizes reality into a psychedelic, imaginative virtuality. Cărtărescu gestures towards science fiction and fantasy, toward autofiction and “reality-based fiction,” and then away, towards a record of anomalies in which reminiscence veers inevitably into dreams and delirium.

Solenoid’s constellation of half-realities extends toward concrete history, too, in the Sebaldian spirit. As an adolescent, the narrator became obsessed with The Gadfly, the late-nineteenth-century romantic revolutionary novel written by Ethel Lilian Voynich. He searches for another copy of the book, which he eventually discovers by chance, and reencountering it proves transcendentally important: “The Gadfly would become my madeleine.” Ethel’s sister Mary Ellen married Charles Howard Hinton, the nineteenth century British mathematician who coined “tesseract” as the name of a four-dimensional cube. Borges’s short story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” narrates how a mysterious cabal of generations of scholars creates an apocryphal tome of the Encyclopædia Britannica for “Tlön,” a fictitious planet which acquires “real” import by virtue of its inclusion in the encyclopedia. The letter detailing this organization’s actions is found enclosed within one of Hinton’s books. The narrator, faced with this dense network of literary and historical references, wonders if parallel dimensional realities could explain his “anomalies.” Cărtărescu is responding speculatively to Proust and Sebald: what if literature, history, and the magic of memory were in fact other worlds?

Solenoid’s solipsistic fantasies coalesce around the “boat-shaped” house on Maica Domnolui Street, which the narrator buys early in the novel. In the 1920s, the house’s prior owner invented a new solenoid and made a fortune healing people with it. He claims that the house sits upon a uniquely intense magnetic field. To channel that energy, he built a gigantic solenoid capped with a chair-like device in a tower attached to the house. The previous owner made other modifications to the house, too: the narrator comes to realize that with the press of a button, the house’s beds allow their occupants to levitate slightly. He uses this mostly for sex with Irina, his colleague. The narrator’s dreams become increasingly outlandish, ever more imaginative and expansive, as though he were in a parallel dimension. But this dream-dimension is terrible, too, soaked in Bucharestian melancholia (“the saddest city on the face of the earth”) and the narrator’s own solitude.

The enchanted and tragic drive of history as our narrator experiences it devolves into ancestral magic and divinity, and he heads to a library to investigate. He intuits some deeper meaning there, some explanation for his “anomalies.” In the borrower’s slip for the copy The Gadfly he gets from the library, the narrator discovers a hidden telephone number. Palamar, the librarian of his youth, picks up the phone and confesses to having left the clue a decade earlier, knowing that our narrator would find it and unleash “a chain of events… which had been planned in times immemorial and which cannot (any longer) be stopped.” What were diffuse intimations snap into sharp focus: our narrator finds himself “at the frontier of the holarchy, where two worlds mirror each other along an asymptotic spiral on a scale neither one of us can imagine.” His visions are intimations of uncountable other worlds, which he is uniquely capable of accessing. What Shields called “reality-based art” falters against Solenoid’s rejection of reality’s solid edge, its disinterest in the real as a tautology or an explanation. Reality zigzags into itself and its others, as though Cărtărescu has settled his literary universe in the cracks between realism, autofiction, and history fiction and far beyond their realm. Shields, we could even say, prefers short books (“about 174 pages”) for this very reason — they’re less threatening, less destructively ambivalent. In a final Kafkaesque turn, our narrator turns into a mite.

Borges’s narrator in “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” discovered Uqbar, a nation within Tlön, in “the conjunction of a mirror and an encyclopedia.” Two parallel and deceitful recreations of the world, visual and textual, play off each other in what we later learn is a grandiose con, the great conspiracy of Tlön, a planet fabricated in a many-tomed encyclopedia. Cărtărescu world of fiction is similarly built of both reality and literature, darkness and light, forever intermingled and unfolding into every direction. An invented object: like the encyclopedia, the library, Bucharest, Buenos Aires, the boat-shaped house, death itself and the enchanted solenoids. The mesmerizing beauty of creation, of reality giving way to itself: that, above all, lies behind the doors of Solenoid.