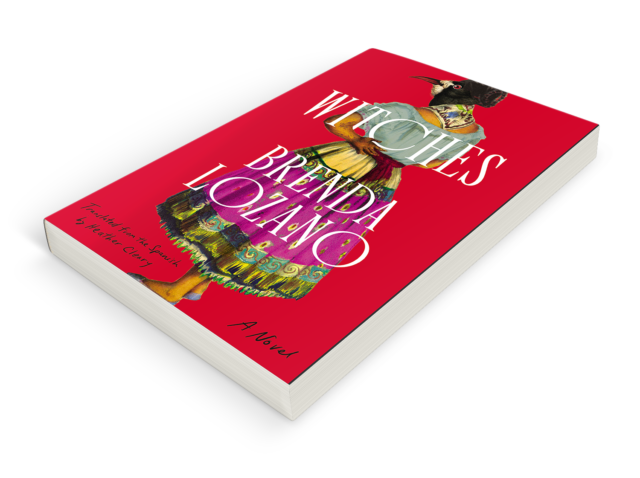

Witches

Brenda Lozano

Translated by Heather Cleary

Catapult, $26

Witches, the latest novel from Brenda Lozano, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary, begins with a murder. In the small mountain village of San Felipe, the body of an Indigenous Muxe woman named Paloma is discovered in a pool of blood. She’d been getting ready for a night out, the residue of eyeshadow still on her fingertips. Zoe, a journalist from Mexico City, is sent to report on Paloma’s death. She accepts the assignment, she says, because “gender-based violence sends me into a rage.” If this opening has primed you for, say, a murder mystery with a feminist bent, as it did for me, Zoe quickly sets you straight: “This isn’t the story of a crime.” She promises us something much bigger, far more profound: a renewed understanding of herself, of her mother, father, and sister, and of the “unfinished business” among them.

The catalyst for these realizations, she says, is an encounter with an Indigenous healer named Feliciana, who is the cousin of Paloma. Before she and Zoe meet, Feliciana’s reputation precedes her; she is, in Zoe’s words, “the most famous shaman alive,” known for performing healing ceremonies that use mind-altering mushrooms. The two women have an instant connection. “I’ll admit I thought I was going to make a difference with my article, that I was going to help someone, but I was the one who found help through my conversation with Feliciana,” says Zoe. “I had no idea how badly I needed it.”

With surprising swiftness, Paloma’s murder fades to the background. Zoe drops any pretense of being an investigative reporter; to her, Feliciana is no longer a source but a sage. From here, Witches slowly unfurls over nineteen chapters, alternating between Zoe and Feliciana’s first-person perspectives, each of them narrating the stories of their lives. Zoe speaks to us in the present, reflecting on her upbringing, her family, her trajectory to this moment with Feliciana. She tells us that “all this, everything that’s written here, is what I came to understand because of her.” Feliciana’s chapters, on the other hand, are presented as the raw transcripts from her conversation with Zoe, a series of recounted stories and memories of girlhood, marriage, motherhood, and her practice as a healer.

Like Lozano’s previous novel, Loop, the enchantingly diaristic account of a young woman living in Mexico City, the first-person narration of Witches is digressive and intimate. We feel as though Zoe is speaking directly to us, and Feliciana directly to Zoe. And it’s a testament to both Lozano’s mastery of voice and Cleary’s translation that our two narrators’ voices feel immediately distinct and immersive. Feliciana’s voice is especially idiosyncratic, at first hard to follow, then, with time, poetic in its fluidity. Her sentences are circuitous and breathless, most of them run-ons several times over, a pure outflow of thoughts and memories. Of her powers, she tells Zoe,

I don’t see the future and I can’t stop a person from dying if death has laid its egg in them and that is the will of God, I can’t do anything about that, but if someone comes to me sick and they can be healed, I heal them because that is to lift someone up who has fallen along the path, people need help to keep moving forward, and lifting us up when we fall is something the Language does.

While translating Feliciana’s periphrastic testimonies, Cleary referenced video footage of the Oaxacan curandera María Sabina, on whom the character is based. “Just as Lozano draws inspiration for her novel from certain details of María Sabina’s life,” she writes in her wonderfully illuminating translator’s note, “I used certain details of María Sabina’s physical and linguistic gestures to anchor my translation.” Together, Lozano and Cleary restore a sense of interiority to Sabina, an influential Indigenous woman whose life and legacy have been repeatedly exploited and flattened by the Western gaze, by creating space for Feliciana to tell her own story.

When it comes to Feliciana’s powers, Zoe is a rationalist but not a skeptic. “I’ve never been into supernatural stuff,” she says at the outset, “definitely not fortune-tellers or whatever.” But she’s had moments with her mother and sister — instances of inexplicable foresight, eerie premonitions — that make her wonder about “the power of intuition.” She remembers her mother telling her once, “All women are born with a bit of bruja in them, for protection.” Moreover, it is Feliciana’s resilience and humility, rather than her purported spiritual abilities, that move Zoe.

In their time together, Zoe and Feliciana find that their shared experience of womanhood transcends their cultural differences. Throughout both their lives, expectations for women have been prescribed. When young Zoe wants to take up playing the drums, she is turned away by a male music teacher in a Nirvana T-shirt who claims that “women sing, they don’t play instruments — and definitely not the drums.” Zoe’s mother sets her straight: “What a monumental idiot, Zoe, with those stereotypes about women,” she says. “You’re not telling me that dumbass killed your interest in playing the drums, are you?” Meanwhile, a young Feliciana questions her abilities as a healer, because healers are traditionally men, and she is the first woman born to a long line of male healers. “You have it, love, you just don’t know it yet,” she remembers Paloma assuring her. “You’ll be frightened because it’s frightening to know the things you’re capable of.”

Both women have also contended their whole lives with the pervasive threat of sexual violence, and their sisters have experienced it firsthand. In detailing those disturbing accounts, Lozano writes with great command and clarity. Zoe and Feliciana bond over their common role as older sisters, a responsibility they treasure. “I wouldn’t be Feliciana if I didn’t have my sister Francisca, just like you wouldn’t be who you are without your sister Leandra” she tells Zoe. “Sisters are what we are not, they have what we don’t and we are what they are not.”

Several times throughout Witches, I recalled a line from Loop, in which the unnamed narrator reassures us, “Don’t be alarmed if this isn’t going anywhere.” Indeed Loop doesn’t end up going anywhere, but that never poses a problem because Loop, unlike Witches, never promises to go somewhere. At the start of Witches, Zoe promises us a reckoning, a revelation. It never quite materializes. Early on, she says her conversation with Feliciana has transformed her perspective, though by novel’s end it remains unclear exactly how — the connective tissue between their two stories is tenuous, their symmetries never fully teased out. And at the tail end of the novel, Feliciana invites Zoe to participate in a series of ceremonies, insisting that Paloma had in fact brought Zoe to San Felipe in order to resolve her aforementioned unfinished business. But the ceremonies, which I imagine would be rich grounds for psychological and spiritual exploration, occupy just three pages.

When it comes to Zoe’s arc, the question of the novel’s unkept promises might be attributed to a narrative swerve at the beginning of the book. When we first meet Zoe, she tells us two things about herself: that she is a journalist and that she is incensed by Mexico’s epidemic of femicide. If the subject matter nudges the reader toward the idea of a social novel, then Zoe’s vocation evokes the crónica, a hybridized and distinctly Latin American form of journalism, favored by renowned Mexican writers like Carlos Monsiváis and Elena Poniatowska. But Witches is a novel, not a piece of reportage, and on the whole Lozano doesn’t so much make critiques as gesture toward them. Her protagonist Zoe’s introductory remarks are the last we hear of her political convictions, and the scope of her inquiry — like that of Loop’s narrator, who is notably not a principled reporter but an aimless, navel-gazing writer — never extends beyond the confines of her own life.

Yet, despite all this, Witches sets the ideal stage for Lozano to prove herself as a master of character study. Zoe’s chapters are particularly compelling — she is, like Loop’s narrator, an authentically-rendered modern woman, and you can’t help but feel invested as she reflects on her first job, her first abortion, her love of poetry, her love of The Simpsons. And while the precise nature of Zoe’s epiphany, and the role of Feliciana as facilitator, is still nebulous by novel’s end, the overarching theme feels crystal clear. It is, to put it crudely, that women should do — or at least try to do — precisely what they want, no matter the external pressures, expectations, or barriers they face. It’s not exactly a groundbreaking idea, sure, but it is, throughout Witches, quite elegantly illustrated.

At one point, Zoe remembers, growing up, when she made good grades or achieved something of note, her mother would say, “I expected nothing less of you.” The phrase weighed heavy on her for a long time — the pressure it implied, the perfection it seemed to demand. One day, a twenty-something Zoe returns home with good news: she’s just been accepted to a prestigious fellowship. Her mother responds with a characteristic “I expected nothing less of you.” It’s then that Zoe understands: “It was her way of saying that doing what I wanted was exactly what she expected of me.” From Lozano, too, we can expect nothing less.