I hear about The Man Without Qualities from Vanya, because of course I do. There are those who write novels and those who write about novels, but only Vanya is life and death about literature without professionalizing. When I meet him, he’s nine months into his new life, emaciated with focus. He’s dropped out of his masters and signed up for unemployment benefits so he can devote himself more fully to his purpose, which is reading every book that matters.

Vanya makes everyone else’s life look like a joke. He refuses to do anything he doesn’t want to do, which is basically everything: working; studying; leaving his flat if it’s raining hard; going to parties, bars, stupid art shows, certain restaurants, certain neighborhoods. He makes this look very easy, very rational. If I want to see him, I have to pay court to him at his room in the east of Leipzig, which is just a mattress on the floor and a pile of books, and he will heat me up a day-old cup of coffee in the microwave and present it to me with a little flourish, like it’s champagne.

He tells me about The Man Without Qualities on a walk. It’s extremely long, he says, and very funny, and it’s about everything but especially about the impossibility of reaching a single coherent decision. I am only half-listening because I’m piecing together the end of a grocery list in my head, looking at a woman’s gray patent leather ankle boots across the street. It’s possible I have ADHD, but who doesn’t think that about themselves, and maybe I’m just a garden-variety narcissist. He grips my arm to get my attention. You have to read it! It’ll change your life!

Ulrich, the titular qualityless man, is a contrarian who attempts to take a year out to do some thinking. At first I find the novel compelling in how contemporary it feels — a surprise since it was published in three volumes between 1930 and 1943. Later I decide that the novel doesn’t feel contemporary as much as it feels weirdly and persistently millennial. Thirty-two-year-old Ulrich moves back to Vienna after a long period abroad trying out and abandoning various professions. His father is scathing about his son’s status in life — unemployed, directionless. For most of the first volume, Ulrich half-heartedly sleeps with a woman who is in a relationship with someone else; he struggles to locate the energy to break it off. Only with the help of his father and coincidence does he also end up embroiled in what feels vaguely equivalent to a mediocre tech company: the Collateral Campaign, a project with an enormous amount of financial backing and no clear idea at its center.

I spend three years reading The Man Without Qualities — which tallies at 1264 pages in my edition — meaning it takes me three times as long as the novel’s one-year plot. I read it in little sips, largely on public transport. I keep needing to restart because the story is too slippery to stay in my head when I lay the book to one side for a week or two. My then-boyfriend lives in Leipzig and my job and flat are in Berlin. It feels like I’m always reading the first two hundred pages on the bus ride between the two cities, as scrubby patches of trees scroll by. “Are you still reading that book?” asks a friend, laughing. “Are you going to take longer to read it than Musil took to write it?” Possibly!

The novel takes place in 1913–14 and the aforementioned Collateral Campaign, which interrupts Ulrich’s year of rest and rumination, is a project to create a year-long celebration in 1918 of “seventy years of peace” under the Austrian Emperor’s reign. The situation is wonderfully farcical: we know the campaign is doomed since by 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire will have collapsed, and Europe will be embroiled in World War I. But even within the Wendy-house safety of the novel’s timeframe, a nothingness infects matters: despite seemingly infinite manpower and resources, the group struggles to concoct a single idea that could form the heart of the campaign.

Eventually, a journalist riffing off the rumors he’s heard about the campaign, coins the term “the Austrian Year” and Ulrich’s cousin and colleague, Diotima, expands on this — it will be a year in which the campaign ensures the whole world feels the peace and harmony that constitutes Austrian life. But even this is a bit of a swindle: as the banker Leo Fischel puts it, “What is true patriotism, true progress, the true Austria?”

Leo’s second question resonates. Vanya is not exactly right: If The Man Without Qualities is about anything at all, it is about a tug of war between science and the arts. The Vienna of the novel is diced up into two camps: people who consider the world through the lens of science (reason, logic, exactitude, certainty) and those who consider it through the arts (emotion, soul, vast swathes of uncertainty).

Ulrich — formerly an engineer and a mathematician — seems, at first, like a reliable proponent of reason. He is constantly asking the drawing-room intellectuals he meets to clarify what they mean exactly by their gauzy statements, something which reliably enrages them. This sets him apart from characters like Diotima, who runs an intellectual salon and is “as capable of uttering the words ‘the true, the good and the beautiful’ as often and as naturally as someone else might say ‘Thursday.’” The novel reserves its sharpest satire for the arts-aligned characters, suggesting its allegiance lies with voices of reason, not emotion.

But something complicates this narrative. Even though it makes fun of the sort of person to whom “something unutterable is always happening,” the novel itself gestures at exactly that. At the heart of the novel lies a something that occupies a space beyond reason and logic, something which is difficult, if not impossible, to put into words. The novel itself functions as the sort of mission statement Diotima might issue: about life being too big and messy and extraordinary to capture in language.

Around the time I finish the unfinished novel (Musil died before giving it an ending), a friend Whatsapps: Have you seen this? It’s a link to a tweet: a day earlier, a German poet — Fabian Navarro, inspired by an idea by Elias Hirschl — has engineered a new version of the text, Die Eigenschaften ohne Mann (The Qualities Without Man — a reversal of the title). The poet, presumably as proficient in IT as he is at verse, has programmed an adjectives-only, adverbs-only version of the text.

Lot of work to set up a one-liner!

I marvel at this algorithmically-revised text for a moment, before returning to the rabbit hole of writing about the original novel. Except nothing really resonates. A lot of the essays about Qualities dissect one or other of the ideas or arguments showcased in the novel and situates them within a broader philosophical understanding but this feels beside the point. Nothing seems to cut at Qualities’ hypnotic quality. The best moments in the novel do not advance the plot, nor do they develop the characters. They are replete with emotion, but it’s impossible to pinpoint what the emotion is:

… once in such a night Ulrich opened the windows and looked out among the tree trunks, smooth as snakes, their twisting tops and on the ground, and suddenly felt an urge to go down into the garden just as he was, in his pyjamas; he wanted to feel the cold in his hair … And then the darkness towering up between the tree-tops suddenly, fantastically, reminded him of Moosbrugger’s gigantic form, and it seemed to him the naked trees were queerly physical — ugly and wet as worms and yet somehow making one want to embrace them and sink down beside them with tears on one’s face.

I am reminded of an essay the critic Greil Marcus wrote that cited the French sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s investigations into the everyday. Marcus notes that it was “no mere sense of mode that led Lefebvre to open his third volume [on everyday life] with a long rumination on Ulysses” (a novel often compared to Qualities) and that Lefebvre believed that social theorists “had to examine not just institutions, but moments — moments of love, poetry, justice, resignation, hate, desire … [he] insisted that within the mysterious but actual realm of everyday life (not one’s job, but in one’s life as a commuter to the job, or in one’s life as daydreamer during the commute) these moments were at once all-powerful and powerless … The rub was that no one knew how to talk about such moments.” It feels like these same moments — moments at the margins around the events in our lives which are supposed to be decisive, but aren’t — form the heart of Qualities.

Now I wonder if The Qualities Without Man might provide a way of drilling to the center of novel. By rereading the book in adjective form only, I could make sense of it in the same way I might an abstract painting, letting my vision blur and refocus, considering it intuitively rather than analytically.

The woo woo–ness of this method feels on the money, given the spirit of the text itself. In the final volume of the novel, Ulrich tells his sister “that ‘being right in the centre,’ a state of undisturbed ‘inwardness’ of life — if the expression isn’t taken in some woolly sentimental sense … is probably something that can’t be demanded in a rational frame of mind.”

Life is chaos. In other words, I immediately hit a wall: an adjective can mean a few different things, and context often supplies meaning. With the context scalpelled away the descriptors become opaque. Not to mention that, while I had read the novel in the English translation, the adjectives-adverbs version is only available in German. Feierlich could be solemn or celebratory, reizend could mean lovely or it could mean irritating. Isn’t it just going to be pages and pages of gobbledy-gook, my younger-not-youngest sister says sensibly, over an inky glass of wine. She’s not wrong: at first stab, I can feel my brain pressing up against the wall of my skull. Slow! Fast! Clever! Sunny! Painful! Wonderful!

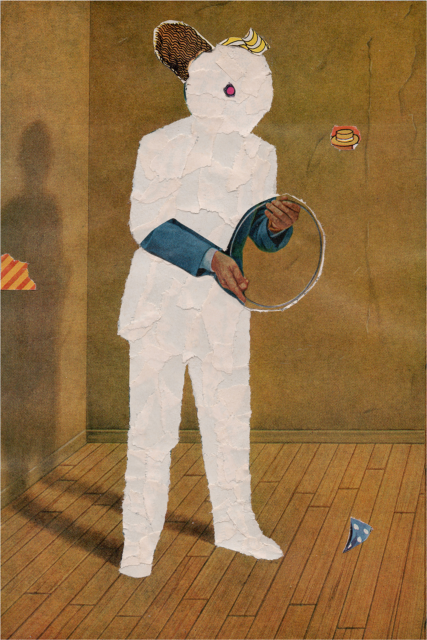

But one day I am half-asleep when I read the PDF and something shifts. The contours of the novel starts to emerge. The Man Without Qualities just so happens to have a distinctive texture. Musil’s prose is a pile of ballet slipper–colored tulle. It is over-ripe fruit, sugar congealing at its center.

There’s a persistent stream of adjectives and adverbs which deny the reader firm ground: weich (soft) and variations on this word (bauchigweich, belly-soft; weichwollig, woolly-soft). His world inhabits a soft remove from the reader: things are floating, shadowy, tender, fluid, blurred or indistinct, shimmering, glimmering, slippery, veiled (schwebend, schattenhaft, zärtlich, fließend, verschwommen, schimmernd, flimmernd, schlüpfrig, verschleiert). Other extra-soft adjectives might appear only once or twice, but to great effect: opalisierend (opalescent), umwölkt (cloudy, but with the “um” suggesting the clouds are pressing in around you in contrast to more common words for “cloudy” like wolkig or bewölkt), wogend (billowing, undulating). Even loneliness is softly rendered: someone or something is einsamkeitsüberglänzt (glossed over with loneliness — I imagine the loneliness like the sugar syrup on the surface of a donut), another moment is mondlicheinsam (moonily lonely).

The counterpoint to this plunging softness is the novel’s abundance of filing cabinet words. Each page is studded with nationalities (Austrian and Hungarian, obviously — but also fair amounts of Prussian, Italian, you name it); there are religions and schools of religions (Jewish, Protestant, Catholic), systems of thought (philosophical, political, historical-political, constitutional, societal, moral, religious, scientific, artistic).

Initially the filing-cabinet words feel like not much more than evidence of the novel’s vaulting ambition — the very thing that meant Musil died with it unfinished; the desire to depict, not just some guy, but everything and everyone surrounding him, sprawling out to the edges of the universe (or what once probably felt like an entire universe: Vienna at the outset of the twentieth century). But it comes to me in a rush that the filing-cabinet words are the door frame: the attempt to impose order and intellectual rigor on the softness of life itself. Qualities acknowledges the constraints of reality — that, as the narration would have it, “If one wants to pass through open doors easily, one must bear in mind they have a solid frame.”

But perhaps more important for the world of the novel than that door frame, is “a sense of possibility.” If a person possessing a sense of possibility is told that things are a certain way, “then he thinks: Well, it could probably just as easily be some other way.” Qualities describes Möglichkeitsmenschen — perfectly rendered in the Eithne Wilkins/Ernst Kaiser translation as “Possibilitarians” — who live “within a finer web, a web of haze, imaginings, fantasy, and the subjunctive mood.” While Ulrich is clearly the novel’s leading Possibilitarian, this mood infects each and every one of the characters as the novel churns on. General Stumm von Bordwehr, a military man who begins the book with an addiction to clear, black-and-white thought, ends it talking like everybody else:

“But you know, a hangman’s a disreputable fellow, there’s no denying that. Yet the rope manufacturer who only supplies the prison with the ropes can be a member of the Ethical Society. You don’t bear that sufficiently in mind.” “You’ve got that from Arnheim!” “May be. I don’t know. Nowadays one’s mind becomes so complicated,” the General lamented sincerely.

So while the novel see-saws between hard and soft, ultimately, it is on the side of softness, chaos, uncertainty. Ideas are a lovely thing, a gorgeous framework, it seems to say. But in the end, the mistiness of life wins out.

Somewhere along the stretch between beginning and finishing Qualities, I move from Germany back to the UK. Two things are conspicuous after seven years away. The first is that the sort of progressive men who are very careful about everything they say, have, as a collective, possibly at some sort of Annual General Meeting, decided that the word “pussy” can and should be deployed in bed. This is neither here nor there but is undeniably not not funny.

The other thing is this: everyone seems awfully sure all of a sudden. Couples have been together for years and are on course to remain together until the end of time (albeit with polyamory as a release valve); I meet any number of dyed-in-the-wool atheists or theists, zero agnostics; everyone I meet has one very specific solution to Britain’s myriad political ills (the Left should be less academic; the North should declare independence from the rest of the country; we should scrap the First-past-the-post voting system) and few doubts; many have resided in the same city for a decade or longer. A friend who secretly believes herself to be suffering from some obscure and terrible illness discovers she is, in fact, accidentally pregnant thanks to her boyfriend of a few months. She doesn’t so much as flip a coin: they move in together, have the child. I see this full-steam-ahead certainty in university students; friends in their twenties and thirties; parents — people of all ages.

Whenever I talk about restlessness or uncertainty, people often regard me as if from a great distance. I tell a friend I want to pursue three different careers simultaneously, I want to be good at all of them, and he tells me I’m going through a stage, and eventually I will have to choose. I am urged to make decisions, but odds are, I’ll continue much as before — muddling through, feeling things I can’t put into words.

Qualities never goes as far as (earnestly) gesturing to the existence of God, though He makes a few guest appearances in rhetorical flourishes. But a mystical strain cuts through the novel. The world is full of trials and small disappointments, but its ordinariness is streaked through with a sort of magic, Qualities says. At the close of the second volume we watch Ulrich watch Vienna from the window.

… he became aware of how the European’s distaste for vague dreamy emotionalism was once again filling him with its hard clarity; and he resolved to meet this turn of events, if it must be, with all possible precision. And yet, standing there for a long time at the window and gazing out, unthinkingly, into the morning, he still had within him something of that twinkling, sliding intermutation of all the feelings there were.

Speaking of feelings — the twinkling, sliding kind. It’s too flip for words, but the only thing I do feel certain about is this: there’s a richness to uncertainty that’s underrated here. Yes, no, I don’t know, maybe — forever and ever, amen.